Exploring Vietnam’s Food and Flavours

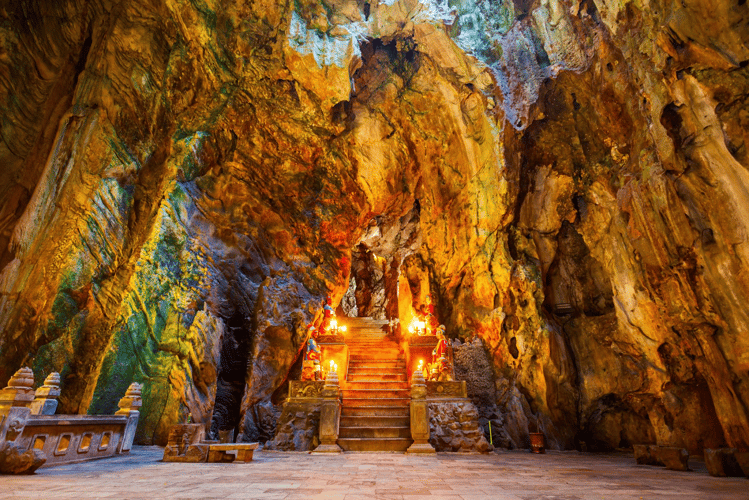

The South-Asian country of The Socialist Republic of VietNam, simply shortened to Vietnam, is celebrated for its thousand-year-old history and green-landscaped richness. Travellers have swamped the fertile land in search of surreal tranquillity whilst exploring mountain peaks through coiled trails, meandering through lush rice fields, reclining on cosy chairs near pristine lakes and rivers, finding ancient treasures of pagodas and palaces sprinkled at every corner, or taking in surreal views quad-biking over red and white sand dunes. The heritage-abundant land, however, is as acclaimed for its gastronomic delights as its topography and customs.

There are several ways to drown oneself in local culture. Imbibing native fragrances and flavours perhaps, take the top spot in truly enjoying an absorbing experience. The Vietnamese populace is known for its friendly approach towards tourists and takes pride in extending a hospitable arm to its guests. The ideal ‘Asian’ way of looking after guests is by whipping up luscious meals and what better way to experience the tastes of Vietnamese cuisine than trying the home-grown food guided by an all-knowing local host?

Vietnamese Cuisine: A Union of Sweetened Sourness with Spicy Aromatics

The local fare in Vietnam is a blending of the five essential senses – taste, sight, smell, touch, and sound – with natural elements: spicy (metal), sour (wood), bitter (fire), salty (water), and sweet (earth). This is based on the five-point philosophy where each taste bud corresponds to vital body organs and colours: the large intestine (white), gallbladder (green), small intestine (red), urinary bladder (black), and stomach (yellow). Traditional cuisine is inextricably linked with the usage of fresh ingredients with an interesting play of textures between herbs and vegetables. Lemongrass, bird’s eye chilli, Saigon cinnamon, lemon juice, basil leaves, ginger, and mint are staples in the Vietnamese diet, and most dishes are rice-based making the food gluten-free, and low in sugar, dairy, and oil.

History:

Historical influences on Vietnam’s food date back multiple centuries when wet rice, herbs, and fish formed an early nutritional base for food – all being abundantly available due to the fertile ground. Several eras later, Vietnam came under the supremacy of numerous Chinese reigns for over a thousand years. The concept of noodles was conceived around this period in China and the original recipe made of millet soon evolved to include new grains and ingredients such as wheat, rice, and eggs, when they were distributed to different provinces under Chinese rule. Unique techniques and methods were used and fresh cooking processes were invented to create innovative meals. Similarly, countless other Chinese dishes such as wontons, pork belly, chow mein, mooncakes, and even grains such as maize and vegetables like chilli peppers, were introduced to Vietnam, where indigenous flavours and styles were added to create ethnic food.

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed French authority on Vietnamese soil with a deep culinary impact on native cookery. Baguettes and crepes, standard fare in French cuisine, seeped in intimately with local food where regional herbs and spices were added to produce dishes synonymous with Vietnamese cuisine today.

Regional Cuisines

The food route in Vietnam is neatly divided into three regions across the country. Although differences in seasoning and components vary, all of them share some central attributes:

- Unprocessed food: Meat is cooked for shorter periods and vegetables are usually consumed fresh. If they are cooked, they are parboiled or lightly stir-fried.

- The abundance of herbs and root vegetables: These constitute the spine of Vietnamese cuisine and are used in plenty in all preparations.

- Alignment and assortment of textures: The Vietnamese menu is filled with a balance and harmony between crunchy with soft, watery with crusty, and mild with coarse food items.

- Soup-based dishes: Broths loaded with vegetables take precedence across all provinces.

- Plating: The predominantly red and brown seasonings, spices, and sauces that complement Vietnamese meals are styled impressively, churning many a hungry stomach for more helpings!

Northern Vietnamese Fare:

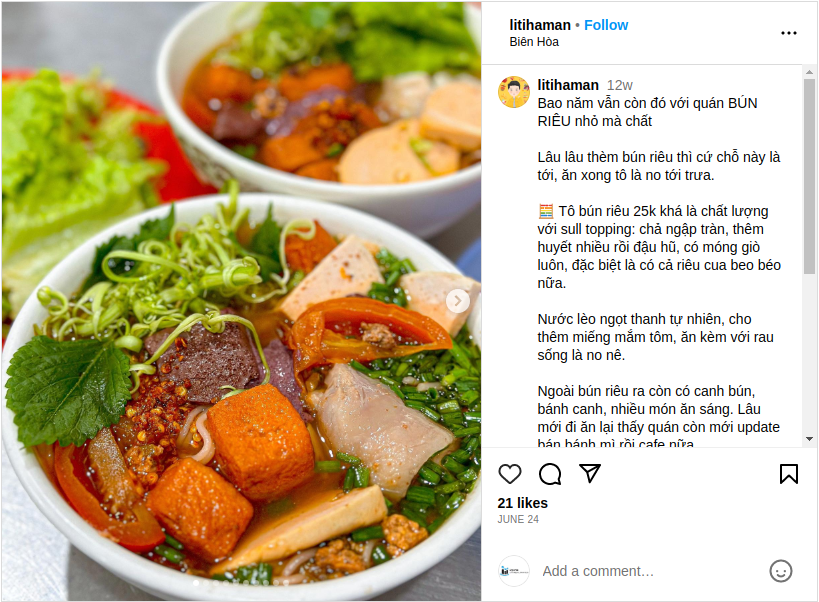

The cooler climes in the north limit the growth and availability of spices. Food tends to be less fiery and black pepper is used in place of chillies as a substitute. Freshwater fish, prawns, crabs, mussels, and squid are prominent stars and several prominent northern Vietnamese dishes are crab-focussed. These are offset with subtle flavours and none of the dishes are overpowered by a singular palate of sweet, salty, spicy, bitter, or sour. The use of meat is much lesser in comparison with other regions and the cuisine is light and balanced. Bún riêu, a traditional crab noodle soup of clear stock and rice vermicelli, topped with minced crab, is one of northern Vietnam’s hidden gems.

Central Vietnamese Fare:

The mountainous terrain is copiously crammed with a variety of spices. Central Vietnam’s cuisine is notably spicy, setting it apart from the other two provinces. Additionally, the food here is treated as an art form that is colourfully presented. Hue, an ancient imperial city, and administrative capital of Vietnam for about 150 years, was home to regal oriental and contemporary occidental culinary influences over many decades. Elaborate preparations served with smaller portions, reflective of past royal influences, dominate the food. Chilli, peppers, and shrimp sauces are frequently used. Bún bò Huế, a popular central Vietnamese dish, is a fiery and rich soup layered with a fistful of flavour. It is paired with slices of beef and pork, and covered with fresh herbs.

Southern Vietnamese Fare:

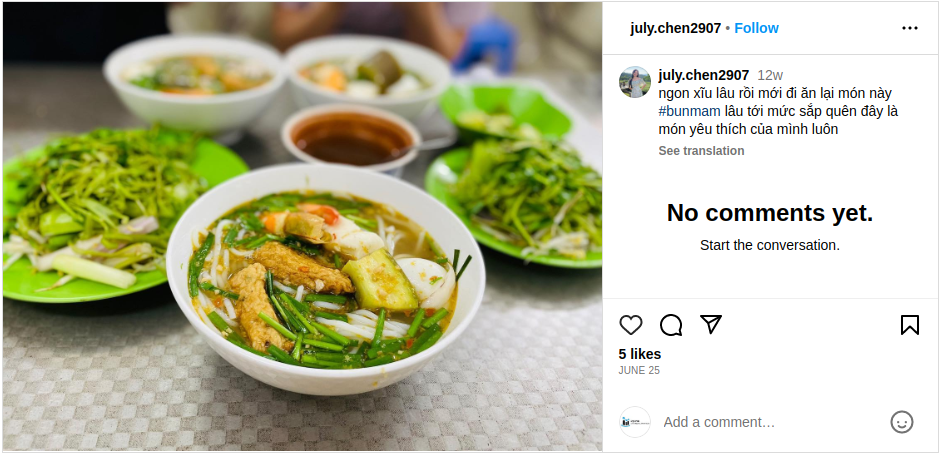

A vibrant assortment of fruits and vegetables thrive in southern Vietnam due to the warm weather and high-yielding soil. The extended coastline makes seafood an organic choice with a generous use of garlic, onions, and herbs. There is partiality for sweet food as compared to the other regions and this is reflected in the liberal use of coconut milk in the full-flavoured cuisine. Bun Mam, a popular dish in the region is a fermented fish noodle soup delivering a snappy kick to the nose but steadies the flavouring with a light broth, herbs, and an array of toppings including crackling pork, prawns, and stuffed whole chillis.

Hanoi: Leading from the Nose

The ancient city of Hanoi has been in and out of favour for being the capital city in Vietnam’s history. It re-surfaced as an administrative centre under French rule and was made the capital once again. Hanoi holds a deep cultural and culinary tradition with the common local greeting being ‘Ăn cơm chưa?” meaning “Have you eaten yet?” Amidst its medieval buildings, mysterious folklore, endless lakes, and racing motorbikes, the shrill sound of street hawkers echoes in the air. Roving through the streets of the Old Quarter fills one’s nostrils with aromas from afar and boiling pots with scrumptious meals beckon at every corner. Many of Vietnam’s renowned and full-bodied dishes were invented here, and chefs routinely list Hanoi as a land of culinary exploration with an ideal merger of Vietnamese, Chinese, and French elements. Enrolling in a cooking class or more popularly, taking a street food trail here to sample local delicacies, finds a top spot for most travellers.

Pho:

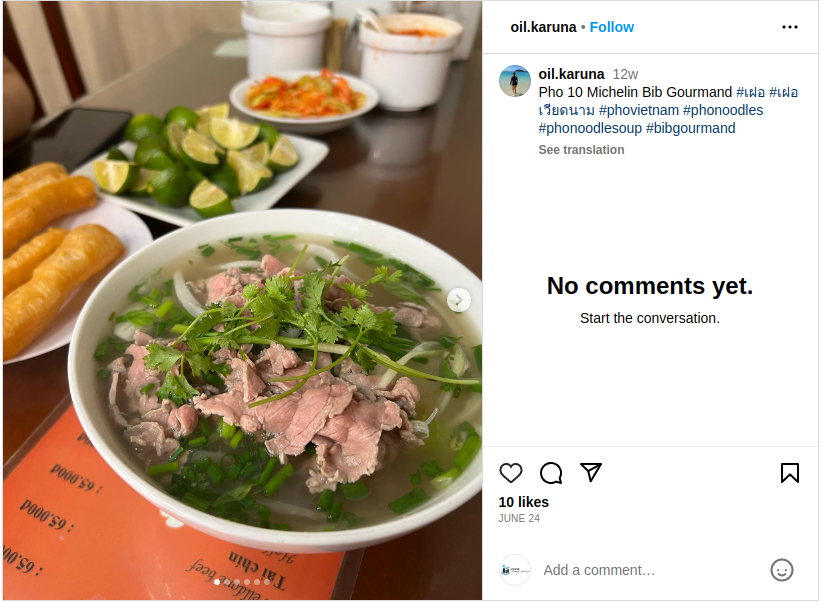

Vietnam’s national dish, Pho, has garnered a prime position as one of the Top 5 Street Foods in the world. A healthy, clear rice noodle soup often eaten at breakfast, pho is a savoury concoction of finely sliced beef or chicken with stock, ginger, cinnamon, black cardamom, star anise, and fish sauce. It is served with herbs, raw vegetables, and lime wedges. Hanoi offers two types of this famed soup – Pho Ga, with chicken, and Pho Bo, with beef. The synthesis of Vietnamese noodles and herbs with a French beef broth is the probable origin of the original soup. The word pho has French roots where pot-au-feu translates to ‘pot in the fire,’ where beef bones and vegetables are boiled in water, with the meat added later to make the perfect broth.

When Vietnam was split into two at the Geneva Convention in 1954, many Vietnamese from the north moved to the south carrying their recipes with them. Due to the fertility of the southern land, there was a platter of choice of raw ingredients and produce. Chefs began to experiment with different seasonings and herbs, and vegetables, adding lime, and bean sprouts to the mix. As a result, the soup became spicier and more sour. It is this version of pho that is now globally recognised and is reminiscent of excellent Vietnamese food.

Gỏi cuốn:

The Vietnamese spring roll holds a prized position for the Vietnamese and was voted one of the best dishes in the world by CNN. A burst of flavour, Goi Cuon is a rice paper roll stuffed with various fillings such as pork, prawn, vegetables, and rice vermicelli fillings, served with a tangy peanut sauce. There is some debate in food circles regarding the origin of the dish. Some food writers credit the culinary influences of China, and others debate that the Goi Cuon is wrapped in Vietnamese rice paper called Bánh tráng. Either way, it is one of the most recognised foods of Vietnam.

Banh Mi:

The legacy of French cuisine in Vietnam’s food history continues with Banh Mi. Born in the 1950s after the French had left Vietnam, the dapper little wrap packs a neat punch and is made with a crusty bread filled with marinated meats, seafood, paté or eggs, herbs, pickled vegetables, and chilli.

Bread and baguettes were introduced to Vietnam by the French but remained exclusive to French recipes and people. However, after the French defeat, the Vietnamese were free to revise the formula to include local elements replacing butter with mayonnaise and expensive cold cuts with vegetables. The resulting sandwich soon became an affordable staple.

Bun Cha:

Distinctive in taste, Bun Cha is easy to track with its strong aroma wafting through the corridors of Hanoi’s streets calling out to a hungry stomach. It is an iconic dish of grilled fatty pork or cha served over white rice or vermicelli noodles, or bún, and fresh herbs with a side dish of a delectable dipping sauce. The pork is deeply marinated in a sweet and sour mixture of fish sauce, sugar, and garlic. A popular lunch choice, it is easy to spot with the small clouds of billowing smoke from charcoal grills which are busy searing fatty pork. Its soaring popularity was aptly described by food author Vu Bang in 1959 who said Hanoi was a town “transfixed by bun cha”.

Nem Ran:

Previously a dish for special family gatherings and occasions such as Tet or the Lunar New Year, Nem Ran, or fried spring rolls, is now served throughout the year. Prepared slightly differently in the three regions, the key essentials consist of lean minced pork or beef, sliced mushrooms, glass noodles, thinly chopped carrots, spring onions and red onions, and duck or chicken eggs. Dried shrimp is sometimes added for extra flavour. The food components are seasoned with salt and pepper and then wrapped with thin rice paper and fashioned into small rolls, which are fried until they are a deep golden colour. The dipping sauce accompanying the rolls is made of fish sauce, umami, salt, lime juice or vinegar, sugar, and chilli. Nem Ran is always served with herbs and vegetables including cilantro and lettuce. Modifications of the conventional pork-based fried roll, such as Crab spring rolls or Nem Cua Be have evolved over time. The crisp texture is balanced with succulent stuffing and a sharp sauce. In Vietnam, the dish is emblematic of tradition and skill.

Ca Phe Trung:

The French War created a paucity of milk in Vietnam in 1946. Seizing an opportunity, a resourceful hotel bartender traded milk for a frothy egg custard as a substitute, birthing the traditional Vietnamese coffee or Ca Phe Trung, which was an immediate triumph. The original recipe has developed and fine tuned over time and today the egg coffee is made with egg yolks, sugar, condensed milk, and coffee. Creamy, thick, and sweet the celebrated Ca Phe Trung egg coffee weaves its magic through hot and cold variations, where the latter is spooned off – much like a dessert. The local tip for the hot cup preparation is to drink it whilst it is warm and not stir it constantly as that leads to the coffee becoming cool rapidly.

Kem Xoi:

The model cool dessert to beat the sticky Hanoi summer heat, kem xoi is made from sticky rice, fresh ice cream, milk, yoghurt, coconut juice, white sugar, and pandan leaves or la nep. The first step is to prepare Xoi or sticky rice by soaking the special variety of rice for over 8 hours and grinding the pandan leaves with water. The two ingredients are mixed and the resulting xoi is steamed with coconut juice. Next, yoghurt, milk, and ice cream are whisked together until smooth and frozen. Topping the steamed (and then cooled) xoi with the icy mixture, sprinkled with fresh coconut threads, is an ideal way to end a Hanoi food tour.

.png?width=520&height=436&name=Untitled%20design%20(76).png)

Vietnam’s food history is as intricate as it is captivating. The fusion of the East and West has resulted in a cuisine of pedigreed quality with an explosive burst of flavours that are indigenous to Vietnam. The principle of yin and yang plays out in every meal with complementary textures and flavours, contrasting seasons with spices, and maintaining the required balance between the heating and cooling properties of ingredients. Call Offbeat Tracks to take you on a lip-smacking search of Vietnam’s myriad food and flavours.